A large formation of aircraft from the United States Air Force, the Royal Air Force, and the Australian Air Force refueled in the dark before heading into battle.

Fighters of the fourth generation from all three countries worked in tandem with an E-8 Joint STARS command and control plane. This included American F-16 Fighting Falcons, British F-15 Eagles, and European Eurofighter Typhoons. Both F-22 Raptors and F-35 Joint Strike Fighters, in the company of their stealthy escorts, examined the battlefield.

As soon as the formation was being “painted” by several radar arrays connected to surface-to-air missiles and incoming fighters, warning lights and alarms illuminated in the cockpits of each aircraft. Fighters in Russian Su-30 camouflage started closing in on us.

“On the last week of a Red Flag exercise, we really throw everything we have at the Blue Force and replicate the toughest adversary possible,” says Travolis “Jaws” Simmons, commander of the 57th enemy Tactics Group.

One of the world’s most sophisticated air defense networks was defeated by the F-35 fighter plane, which then sent the information to other missile-equipped jets like the F-16.

The F-35 can reach speeds of up to Mach 1.6, and it can store four weapons inside without sacrificing its stealthiness. The F-35’s processing capability, rather than its weapons, is what sets it apart. This is why F-35s are sometimes referred to be “quarterbacks in the sky” or “a computer that happens to fly.”

“There has never been an aircraft that provides as much situational awareness as the F-35,” Major Justin “Hasard” Lee, an Air Force F-35 pilot instructor, told Popular Mechanics. “Situational awareness is more valuable than gold in battle.”

For almost its entire existence, though, people have argued about whether the F-35 is a revolutionary platform or a textbook example of the Pentagon’s wasteful approach to buying weapons.

Actually, both are correct.

A 21st-Century Fighter Jet

The F-35 we know today was designed to be a versatile fighter jet that can fulfill the needs of a variety of armed groups.

Pentagon authorities anticipated that with the introduction of the new “Joint Strike Fighter,” they could simplify logistics such as supply chains, maintenance, and training. The same stealth technology used by the F-22 would be used in this design. Since its first proposal in 1995, the Joint Strike Fighter program has rapidly progressed to two competing prototypes, Lockheed Martin’s X-35 and Boeing’s X-32, in order to meet the extensive needs of the United States Navy, Air Force, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), and, shortly, the United Kingdom and Canada.

The Joint Strike Fighter was tasked with replacing no less than five distinct aircraft across the services, including the high-speed interceptor F-14 Tomcat and the tank-killing close air support A-10 Thunderbolt II.

While it would seem like a good idea to replace all these planes with one, doing so would be prohibitively costly due to the large list of criteria. In reality, many people had doubts that a large number of X-35s could be manufactured when they were still in competition for the contract.

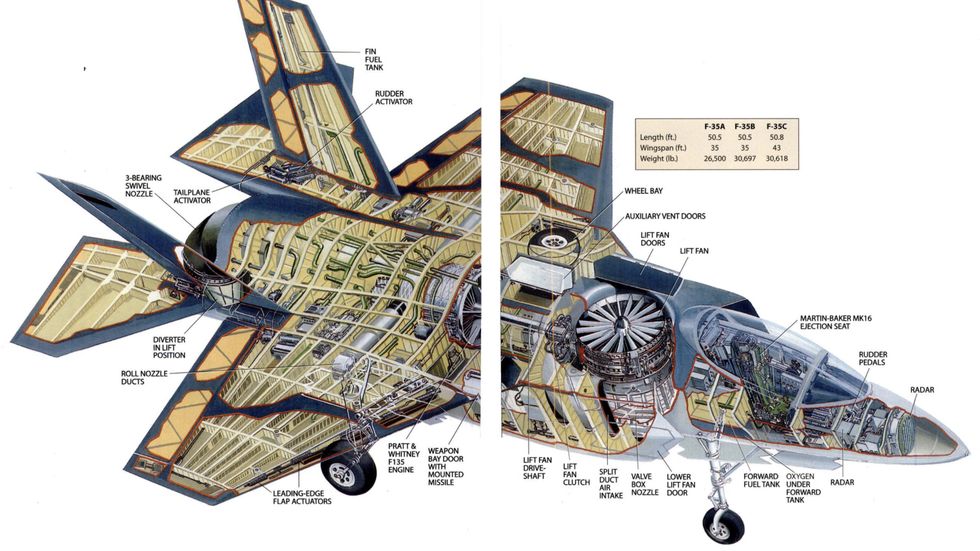

The Specs of Lockheed Martin’s F-35

The F-35 may be the stealthiest fighter in use today since it was built from the bottom up with low-observability in mind.

With its single F135 engine producing 40,000 pounds of power in afterburner mode, this sleek yet hefty fighter can reach speeds of up to Mach 1.6. When operating in disputed airspace, only four weapons can be carried inside, but when flying in low-risk settings, the aircraft may be modified with an extra six weapons installed on exterior hardpoints.

The F-35A has a tiny door on the inside that conceals a 4-barrel 25mm rotary weapon, which helps reduce radar returns.

The F-35 can attack both airborne and ground-based targets with its conventional weapons package of two AIM-120C/D air-to-air missiles and two 1,000-pound GBU-32 JDAM guided bombs. To ultimately accommodate an extra two missiles, Lockheed Martin has built a new internal weapons carriage.

The F-35’s cockpit is a departure from previous generations of fighters, with its enormous touchscreens and helmet-mounted display system replacing the plethora of instruments and displays. The Distributed Aperture System (DAS) and suite of six infrared cameras strategically placed around the F-35 make it possible for the pilot to see out the plane’s windows.

Tom Burbage, Lockheed’s general manager for the program from 2000 to 2013, told the New York Times that if someone had said in the year 2000, “I can build an airplane that is stealthy, has vertical takeoff and landing capabilities, and can go supersonic,” most people in the industry would have said it was impossible. To put it another way, “the technology to bring all of that together into a single platform was beyond the reach of industry at that time.

The X-35’s lift fan design included a drive shaft running from the aircraft’s rear engine to a massive fan mounted in the fuselage behind the pilot. The F-35, like the X-32, would point its engine downward while hovering, but unlike the X-32, it would also draw air from above the aircraft and drive it down through the fan and out the bottom, resulting in two balanced sources of thrust that greatly improved the aircraft’s stability.

It also played a role in the F-35’s aesthetic victory.

Lockheed Martin engineer Rick Rezebek said of the company’s aircraft, “you can look at the Lockheed Martin airplane and say, that looks like what I would expect a modern, high performance, high capable jet fighter to look like,” in a PBS Nova program. When people see a Boeing jet, their first thought is usually, “I don’t get it.”

Although Boeing’s X-32 prototype was more visually striking, Lockheed Martin ultimately prevailed in the race in October of 2001. The F-35’s future seemed bright after its official naming.

Complications and Headaches

Lockheed’s lift fan approach to STOVL flight may have gotten them the contract, but it didn’t mean the work was done.Lockheed’s Skunk Works began developing the F-35A, a variant of the new fighter designed for service by the United States Air Force as a conventional runway fighter similar to the F-16 Fighting Falcon. The F-35A was developed first, followed by the more sophisticated STOVL F-35B for the United States Marine Corps, and then the F-35C designed specifically for use on aircraft carriers.

The only catch was that it was quite challenging to fit all the essential hardware for the many variations into a single fuselage. Lockheed Martin learned their weight estimations for the F-35A were off by around 3,000 pounds by the time they finished developing the Air Force version and began work on the B. This blunder led to a major setback, the first of many.