Before Erik Prince and Yevgeny Prigozhin, the life of mercenaries fighting for a few dollars more in another man’s war was not exactly ideal. Back in the 1970s, the “Circuit†(a term used by Private military companies to refer to their business) was not generally advertised online. Contracts were not corporate-friendly, bosses were not that influential and the daily office routine consisted of dust, sweat, blood, mosquitoes, and shadowy, fragmentized proxy wars that were a defining feature of the Cold War.

One would argue that even today the second oldest profession in the world, fighting as a mercenary, is about the same type of business: Fighting for money. Basically, they are right. But the nature, the essence, and the actual working conditions of a modern-day private military contractor have changed dramatically.

The same goes for his tasks, the budgets involved, his professional training and working experience, his recruitment as well as his actual mission – which is not limited to actual fighting. Of course, the old school stuff still occurs today. But in this article, we are writing about mercenaries. Not start-up entrepreneurs or lawyers.

Back in the 70’s you were not even called a contractor. It was enough to be just a soldier of fortune. Or a war dog. And you would get your chance to be contracted in a hot zone if, during your military career, you were involved in armed robberies, being a little psychotic, beat the hell out of your commander before being dishonorably dismissed from the army or have made your name in actual military action that led to some kind of bloodbath. This is how two ethnically Greek, British Cypriots made their name in Angola during the early days of the Angolan Civil War, creating a long-lasting myth in the mercenary Universe.

Costas Georgiou aka the “the Psycho Colonel Callan†and Charlie Christodoulou aka “Shotgun Charlie†or “Charlie Kebab†are some of the most infamous cold-blooded mercenaries of the 70’s that formed part of a group of mostly British mercenaries that made a one way trip to Angola. Their aim was to combat the spread of communism in the country by joining the ranks of the Western-backed FNLA (National Liberation Front of Angola) and waging war against the MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola).

At its peak, the Angolan Civil War was a chaotic mess between the Soviet Union and the Western powers. It also saw major involvement in the form of Cuba, China, South Africa, the CIA, and other non-state actors including several private military contractors. It was a key case study of a proxy conflict in the Cold War. The war was catastrophic and left 800,000 dead, 4 million displaced, and 70,000 with amputated limbs as a result of landmines.

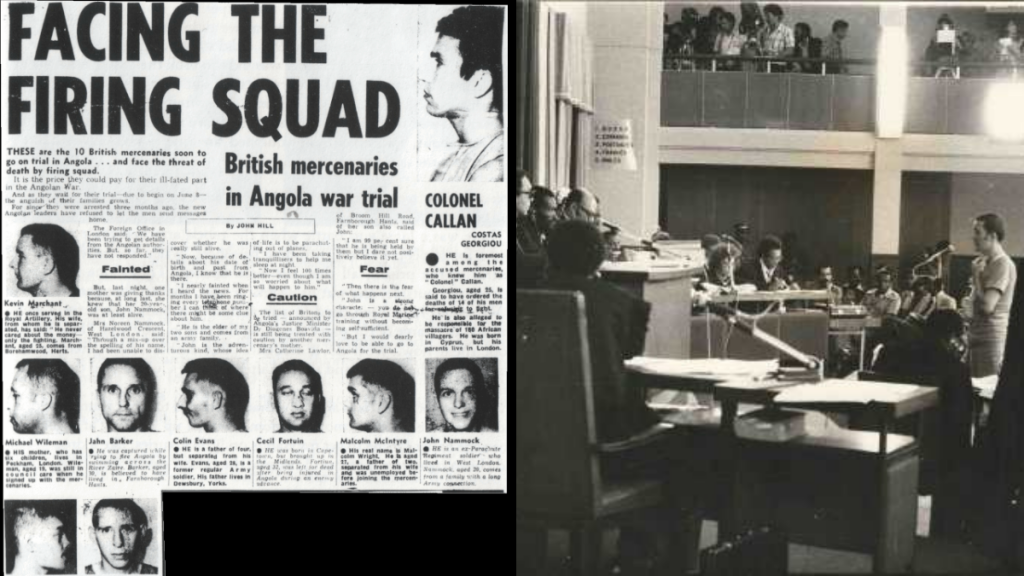

Both Georgiou and Christodoulou, who were not blood-related cousins as it is often written, were linked to widespread acts of atrocities in the war. Georgiou, in particular, was described by British journalist Patrick Borgan as a “psychopathic killer” for executing 14 of his fellow men. Both British-Cypriot mercenaries came to a bad end. Georgiou was sentenced to death in the infamous Luanda Trial and was executed on July 10th, 1976. Christodoulou, on the other hand, was killed in an ambush.

Beyond the myth of the Cypriot mercenaries

The reality and myths surrounding the story of the two Cypriot mercenaries in Angola reveal interesting aspects in relation to the early industry of private military corporations. According to my investigation, we encounter clearly problematic characters that were already notorious crooks within the British Army.

“Callan was a homicidal maniac, who spent a lot of time killing blacks just for fun”

– Costas Georgiou as described by one of his fellow mercenaries

Georgiou moved to Britain in 1963 because his family was involved in treason against the EOKA armed struggle by collaborating with the leadership of British colonial rule in Cyprus. He then went on to sign up with the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment in the British Army before being deployed to the heart of The Troubles in Northern Ireland.

Initially, Georgiou served in the British Army with distinction and it was noted that he quickly became one of the best marksmen in his unit. But on the 18th of February in 1972, alongside other soldiers of his unit, he was involved in an armed robbery on a Post Office and was jailed for five years as a result.

Christodoulou served alongside Costas Georgiou in the same regiment during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. He was similarly the son of Greek Cypriot parents and born in Birmingham in the UK.

Following an honorable discharge from the British Army, Christodoulou would go on to remain on the same path as Georgiou in their ill-fated mercenary expedition to the civil war in Angola. There, he would pick up the nickname “Shotgun Charlie” due to a Spanish-made shotgun being his main weapon of choice and one that he was rarely seen without.

Carnage in Angola

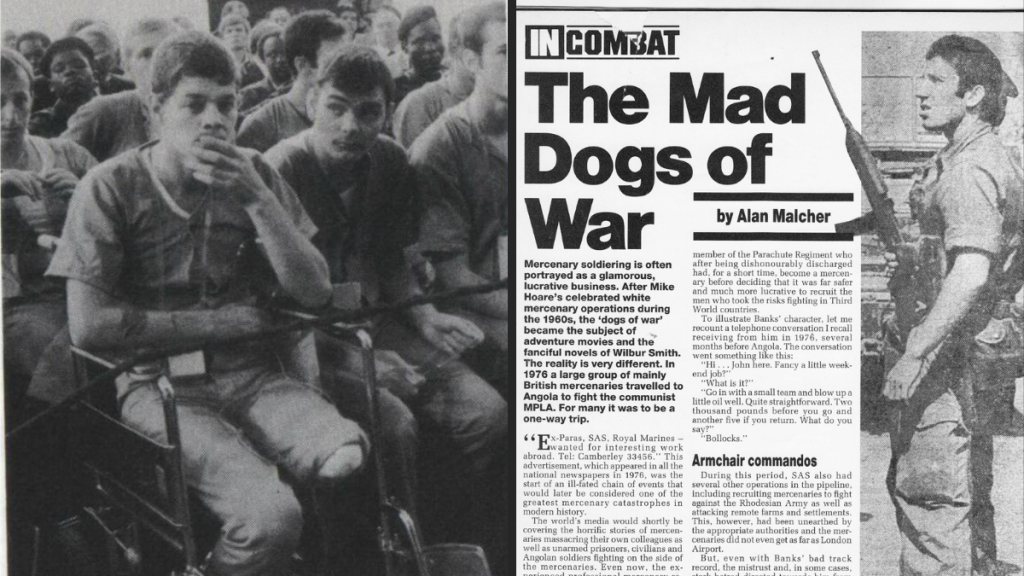

But the line of actual events that took place in Angola, involving the two mercenaries, are complicated and definitely exaggerated by the international press of the time. Not because some guys nicknamed the “Shotgun Charlie†and the “Psycho Colonel†were the best of guys but because they were poorly equipped, under-trained, and engaged in tasks not ready to accomplish with modern-day tactical standards (including the “Circuit†standards).

Whilst the Soviets, Cubans, U.S., and South Africa all got stuck into the Angolan Civil War, various private military companies (PMC) in the UK began recruiting ex-military men to go and fight there. This is how Charlie Kebab, the Psycho Colonel, and a squad of other mercenaries found their way into the conflict.

Poorly equipped and with a lack of leadership skills in the face of crack Cuban and Soviet-trained troops, the PMC jaunt in Angola soon turned to chaos. The process of the unit’s downfall can be narrowed down to the two contingents of mercenaries that arrived in the country headfirst into a broken war.

The first contingent that Georgiou and Christodoulou came with were mostly comprised of professional soldiers including former SAS. However, Georgiou resented SAS’s own leadership structure within the group and saw them as a threat to his position. Over time, Georgiou became violently paranoid towards the people around him which soon created an air of terror amongst his fellow British mercenaries and African troops alike.

Unlike the first, the second contingent of mercenaries was comprised of men with next to no military training or experience. Many quickly hurt themselves during training with weapons they had no experience with. Undisciplined and realizing how much of a dangerous situation they had landed themselves in, these men stole vehicles attempted to escape Angola whilst opening fire on their fellow FNLA troops. The fleeing newcomers were rapidly intercepted by Georgiou’s men and 14 of them were killed by firing squad.

The benchmark of the modern PMC

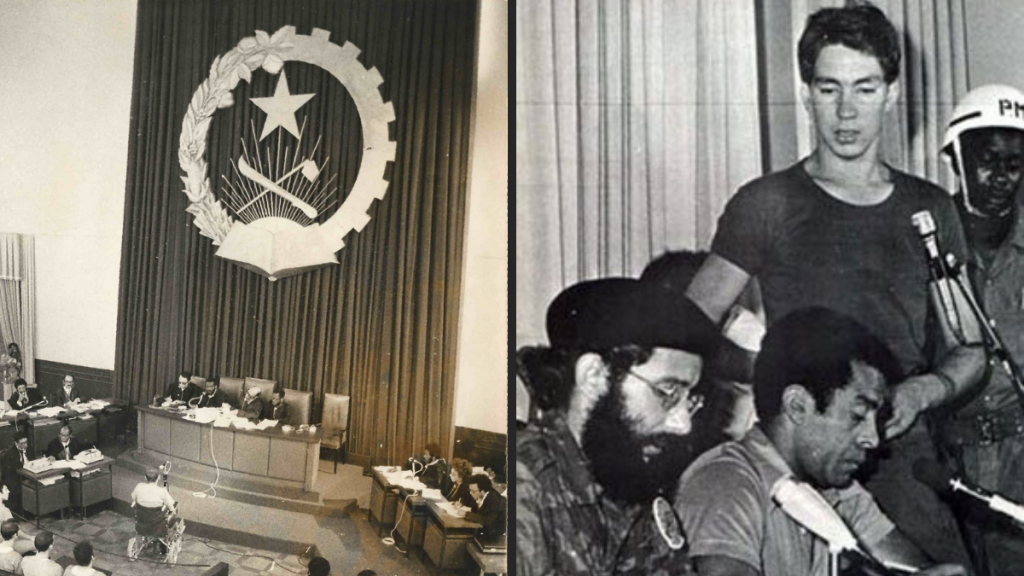

In 1976, Costas Georgiou found himself on trial among thirteen fellow mercenaries from Britain, America, and Ireland. They has all been captured by the MPLA and were taken to court in what became known as the Luanda Trial. Lasting for five days between the 11th and the 16th of June, the guilty verdict had been decided before the trial even began. The only question was what punishment should be meted out on the captured foreign mercenaries.

The majority of men were handed jail sentences ranging from 16 to 30 years. Four of them, including Colonel Callan who was established as killing 170 Angolans, were condemned to death by firing squad. In the years following, the American prisoners were released in 1982 during a prisoner exchange worked out by the United States Department of State. Two years later in 1984, the British and Irish prisoners were released after a deal struck by the British Foreign Office.

In summary, the Luanda Trial produced a strong legal benchmark internationally which is still relevant to the modern-day PMC industry. From Syria to Libya and from Donbass to Mozambique, PMC contractors certainly no longer look like the soldiers of fortune who were operational in Angola during the 1970s. Do they?