The Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1986 had a profound effect on the Intelligence Community’s operations and the conduct of the U.S. Armed Forces itself. Perhaps the primary motivator behind the creation of this Reorganization Act was the disastrous Operation Eagle Claw in 1980.

The mission was devised in response to the November 1979 student revolutions in Iran which resulted in, “[the storming of] the U.S. embassy in TehrÄn, taking 63 Americans hostage. Three additional members of the U.S. diplomatic staff were seized at the Iranian Foreign Ministry. The incident took place two weeks after U.S. Pres. Jimmy Carter had allowed the deposed Iranian ruler, Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi, into the United States for cancer treatment. Iran’s new leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, called for the United States to return the shah, as well as for the end of Western influence in Iranâ€.Â

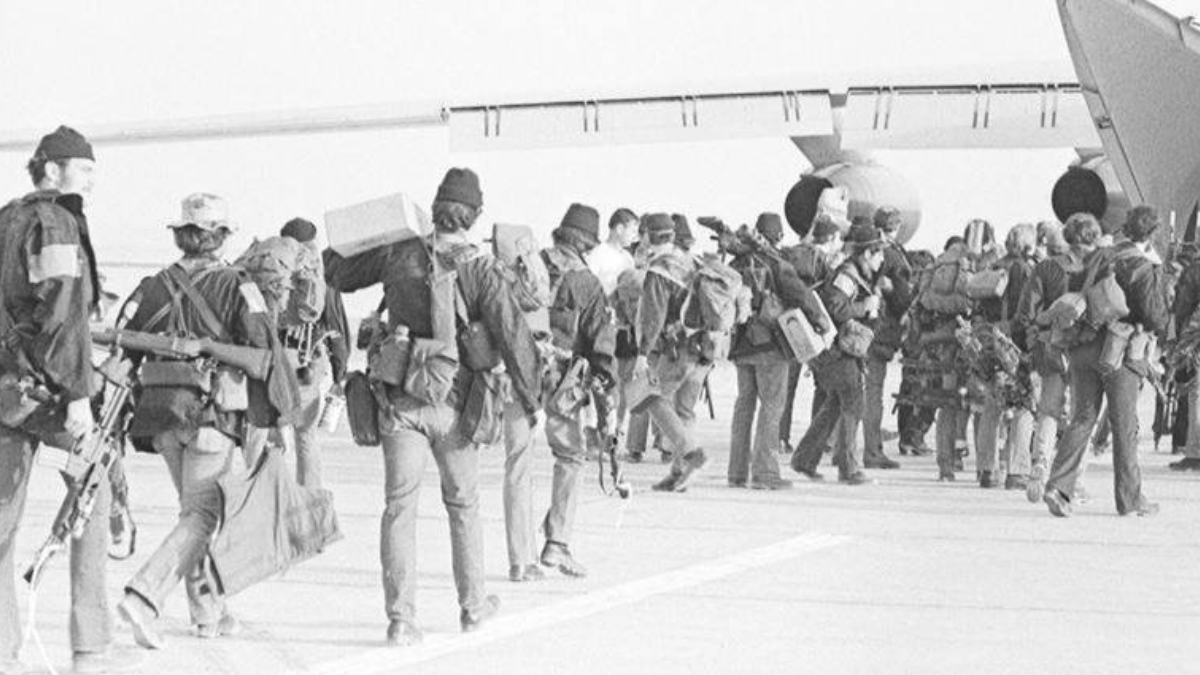

Eagle Claw was planned by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and comprised of special operators from the U.S. Army with aviation, technical, and logistical support from the U.S. Air Force, U.S. Navy, and U.S. Marine Corps. However, “training was superficial†and the operation began poorly, with proper communication between services lacking and each branch desiring a larger role in the operation; to quote from Sean Naylor’s text on the history of Joint Special Operations Command, Relentless Strike, “With the assault force [U.S. Army special operators, U.S. Air Force C-130s, and U.S. Marine Corps Sea Stallion helicopters] already deep inside Iran at a remote staging area called Desert One, President Jimmy Carter had aborted the mission at the commander’s request because only five of the original eight helicopters critical to the mission were still in flying condition. Then, as the force was preparing to return to [base]…catastrophe struck. A helicopter crashed into a plane full of fuel and Delta Force soldiers. Eight servicemen and all hopes of merely postponing the rescue attempt until the next night died in the resulting fireballâ€.

The following political crisis made attempting another mission impossible, resulted in the U.S. Armed Forces being perceived as inept, and showcased the problems inherent in the U.S. Armed Forces.

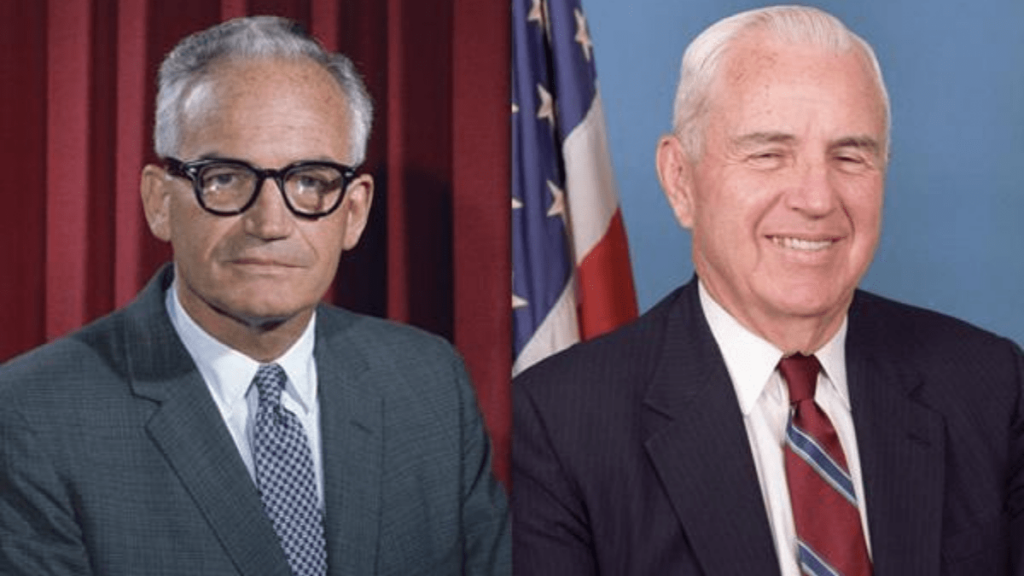

Following the disaster and the Joint Chiefs of Staff independent report (along with the 1983 invasion of Grenada and the U.S. Marine barracks bombing in Lebanon), the unified combatant command United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) was created, with Senator Barry Goldwater and Representative Bill Nichols both sponsoring a bill named after them both.Â

The bill’s goal was, “To reorganize the Department of Defense and strengthen civilian authority in the Department of Defense, to improve the military advice provided to the President, the National Security Council, and the Secretary of Defense, to place clear responsibility on the commanders of the unified and specified combatant commands for the accomplishment of missions assigned to those commands and ensure that the authority of those commanders is fully commensurate with that responsibility, to increase attention to the formulation of strategy and to contingency planning, to provide for more efficient use of defense resources, to improve joint officer management policies, otherwise to enhance the effectiveness of military operations and improve the management and administration of the Department of Defense, and for other purposesâ€.

The entire goal of Goldwater-Nichols was to reform and redistribute the structure and cooperation between the branches of the U.S. Armed Forces and better improve civilian oversight. While the bill focused primarily on the U.S. military and not the Intelligence Community, the bill did exert influence on IC operations.Â

As noted by Navy intelligence professional and career CIA officer Phyllis Provost McNeil, “The 1986 Goldwater-Nicholas Act…also had an impact on intelligence. The Defense Intelligence Agency and Defense Mapping Agency were specifically designated as combat support agencies, and the Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the DCI, was directed to establish policies and procedures to assist the National Security Agency in fulfilling its combat support functions. The Act also required that the President submit annually to Congress a report on U.S. national security strategy, including an assessment of the adequacy of the intelligence capability to carry out the strategyâ€.Â

Really the goal of this act, for the Department of Defense and the U.S. Armed Forces, was to “[have each of the Armed Services] give up some of their turf and authorities and prerogatives [to achieve better joint capability]â€. As well, similar problems also emerged in the IC when developing the Community’s Centers, their various regionalized centers for intelligence analysis and collection and tactical planning, and task-forces for counterterrorism and other more specific issues (like the breakup of Yugoslavia).Â

As distinguished intelligence professional Lowenthal notes in his book Intelligence: From Secrets to Policy, “Given the location of the centers, however, some agencies are sometimes loath to assign analysts to them, fearing they will be essentially lost resources during their center serviceâ€.Â

Much like with how the Armed Forces did not desire to send attaches to other branches or communicate with others in regards to logistical or intelligence issues, the IC was quite apprehensive to sending their best analysts or officers to serve on task forces that concerned terrorism, narcotics, or regionalized issues and only did so once it became apparent (with the 9/11 attacks) how unprepared the U.S. was to face certain issues. As one can see, this Act did force the Intelligence Community (predominantly those within the DOD) to become more aware of the policies and procedures that could make intelligence effective and assist in cooperation between commands and branches.

A joint requirement would be a good idea for the Intelligence Community. Some of that can already be seen in the federal government, with officers from the CIA acting as liaisons to FBI task forces and divisions (and vice versa) in addition to having high-level CIA officers take charge of entire agencies (like the Defense Security Service, now the Defense Counterintelligence and Security Agency). Having liaison programs like this is only one step toward increased interaction amongst agencies with one another.

Having CIA officers and analysts work closely with members from the Armed Services intelligence commands and with the NSA, DIA, and the DHS’ Office of Intelligence and Analysis would further promote the sense of unity, sharing of information, and foster better relationships amongst agencies that, historically, have been at each other’s throats when competing for more funds or have been cagey when controlling their intelligence apparatuses.Â

Like with Goldwater-Nichols, having an increased civilian oversight of the Intelligence Community would be a benefit and would allow abuses or oversteps to be stopped before they even occur potentially. Many in American society (and abroad) will point to the abuses conducted in the name of national security when mentioning the Intelligence Community or their members and a great many desire that civilian oversight is a key aspect of keeping these agencies in line.

Further Reading

- Targeted Killing or Assassination? Legality in the Death of Anwar al-Awlaki

- 129 Years On: The 1893 Overthrow of the Hawaiian Monarchy

- An In-Depth Look at 10 Famous Traitors in Military History

It is something that the public desires their governmental authorities to have, but it also allows another layer of security to ensure that those past abuses (like the FBI’s COINTELPRO or the NSA’s surveillance of U.S. citizens) do not once again occur and erode the trust that Americans place in their government, the trust that allies put in the U.S. government, and the overall standing that America has in the world.