The phrase “One person’s hero is another person’s traitor†is used often in the discussion of foreign policy and politics. It essentially means, that while some persons may be viewed heroically by one nation, they oppositely are viewed negatively by an enemy nation. Many examples of famous traitors can be found throughout history, most often when looking at a nation’s military, government, or even general society.

For this list, persons who are undoubtedly traitors, like Aldrich Ames or Robert Hanssen, will not be considered as they aren’t members of a military force, but instead are purely members of the government.

“One of the key qualities in any spy is the ability to listen and listen well. Perhaps none better exemplify this than Wilhelm Canaris, one of the most notable and impressive, if understated, spymasters in history.”

In addition, the term traitor must be defined. According to Merriam-Webster, a traitor is “one who betrays another’s trust or is false to an obligation or dutyâ€. For this list, traitors will come in many forms. Some of them will be ones whom I personally believe were exceptional in their duties and betrayed their regime for morally right reasons (Wilhelm Canaris and Dimitri Polyakov are prime examples) while others betrayed their oaths of service and contributed to the enemy (Robert E. Lee for example).

Article Contents

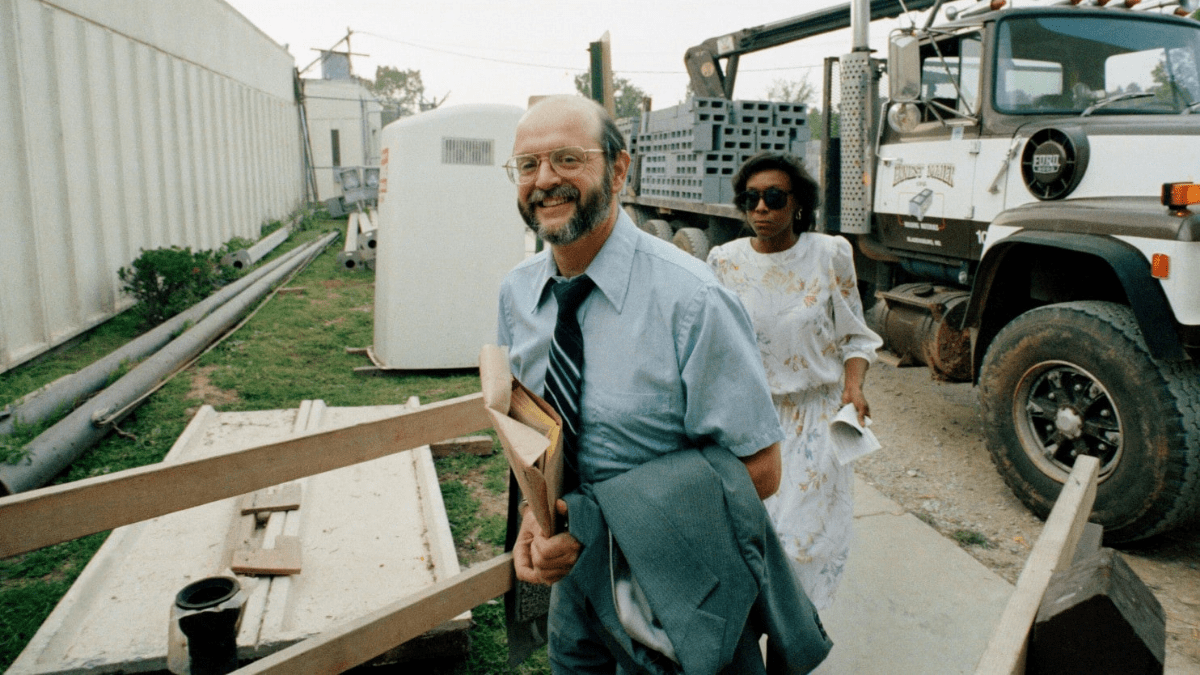

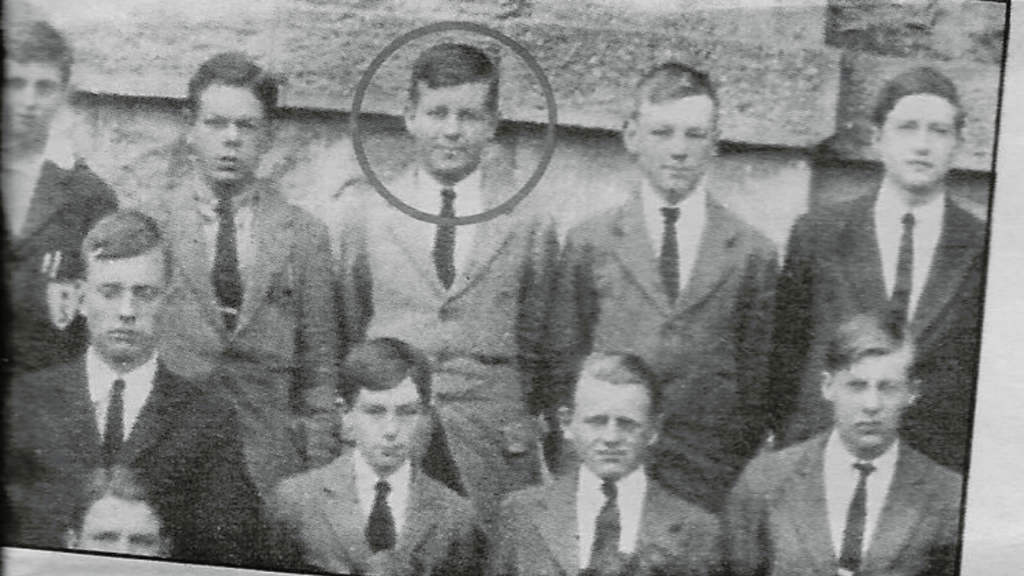

Patrick Stanley Vaughn Heenan

Throughout the Second World War, there were many traitors and spies on both sides, some being more successful than others. One of the more serious, yet little mentioned traitors was Patrick Stanley Vaughn Heenan.

Born in New Zealand, his mother was involved in a relationship with an Irish Republican engineer with the last name Heenan. When the three moved to Burma, Stanley was baptized as a Roman Catholic and took his step-father’s surname.

When Stanley was twelve, his family moved back to England and was educated at the Sevenoaks and Cheltenham Schools where he was regarded as a subpar student, yet excelled at sports. He never received a formal undergraduate education, yet was able to become an officer with the British Army through the Supplementary Reserve between 1930 and 1932.

In 1935, he was officially commissioned into the British Army and was assigned to the British India Army. Some historians have pointed out that this was common with British officers who performed unsatisfactorily, though it must also be noted that Stanley did perform well in some engagements.

In late 1941, Stanley and his unit were assigned to British Malaya where he worked as an air liaison where he coordinated British Royal Air Force (RAF), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF), and Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) operations.

At some point, for reasons unknown, Stanley began delivering information to the Japanese. Primarily, this information consisted of specific codes which were changed daily. This would help the Japanese in destroying numerous British aircraft during the invasions of Thailand and Malaya. In fact, most of the aircraft in Malaya would be destroyed.

Stanley was found to be in possession of espionage equipment including a morse code transmitter disguised as a typewriter.

He was court-martialed for treason at some point in January of 1942, yet this appears to be an informal action as the normal punishment for treasonous officers was death.

By February, it had become clear that Britain was going to lose Singapore to the Japanese. Apparently, according to multiple biographers, Stanley had become more assured he would be saved by the Japanese and frequently taunted his captors. British MPs took Stanley and extrajudicially executed him in Kepler Harbor, Singapore.

While Stanley’s actions surely were not the most integral to Japanese victory, they did contribute to the damage. And, perhaps most damagingly, Stanley’s betrayal was severely demoralizing to an already beleaguered British force in Malaya.

Mir Jafar and the British East India Company

While many are unfamiliar with Indian history, Mir Jafar is a name that surely many know. Born Mīr Muhammed Ja’far Khan around 1691, very little is known about his early life or circumstances.

What is known is that he was a general officer and served under Nawab of Bengal Alivardi Khan, controlling the largest district of the Mughal Empire. Due to a tactical error in an important battle against the Maratha Confederacy, MÄ«r was looked down upon by Alivardi Khan and his successor, SirÄj al-Dawlah.

Feeling underappreciated, MÄ«r turned to the British East India Company for assistance in gaining the throne. MÄ«r met with Lieutenant Colonel Robert Clive and provided him with vast quantities of information on SirÄj’s troops in addition to purposefully withholding his troops to allow Clive’s forces to gain a better tactical position. Following SirÄj’s execution, MÄ«r was allowed to sit on the throne as the Nawab of Bengal.

After some political tumult in which MÄ«r was replaced on the throne by his son, he was reinstated as a puppet ruler in 1763, making a series of decisions that ultimately allowed Great Britain to encompass all of India and continually exploit the nation until 1948. Essentially, MÄ«r, due to his own desire to become ruler, allowed the brutal colonization of his nation and descendants upon descendants of his people to occur.

At the end of his life in 1765, perhaps out of guilt and remorse, he was heavily addicted to opium.

Oleg Penkovsky and the Cuban Missile Crisis

Oleg Penkovsky is a name most likely unfamiliar to most readers, except those most entrenched in the history of intelligence and espionage. He nonetheless was an integral figure of one of the most important events of the 20th century.

The son of a White Army (anti-Bolshevik) officer, Penkovsky became a graduate of the Kiev Artillery Academy on the cusp of the Second World War and served in the Winter War and on the Western Front of the Second World War.

A Lieutenant Colonel by the war’s end, he was assigned to the GRU, the foreign military intelligence agency of the Soviet Army and served in Turkey as a military attaché while also becoming close to the head of the GRU.

In 1960, while in Moscow, Penkovksy indicated to the CIA he wanted to provide information, yet help was needed from MI6. In early 1961, Penkovsky met with representatives of both the British and Americans in London and began providing massive quantities of information on ICBMs and Russia’s ballistic and nuclear capabilities.

One of Penkovsky’s most significant revelations was that of Russian missiles in Cuba. This information being passed to the Kennedy administration would enable them to fly reconnaissance planes and confirm the intelligence received.

Two days before President Kennedy revealed that U.S. intelligence had confirmed Soviet missiles in Cuba, Penkovsky was arrested which placed the U.S. at a disadvantage when negotiating with the Russians later on during the Crisis.

The exact manner of Penkovksy’s demise is unknown. It is known he was tried for treason and found guilty by a Soviet court, yet there are multiple accounts of his death; some believe he was shot and then cremated while others assert he committed suicide. As well, his motivations are not the most complex, having told his Western handlers he was upset at the Khrushchev regime, yet also having been passed over for promotion

Nonetheless, Penkovsky remains a noted background figure to the Cuban Missile Crisis and, quite possibly, avoided a nuclear war.

Ryszard Jerry Kukliński

As with some of the others on this list, few will recognize the name of Ryszard Jerry Kukliński. He nonetheless was a key intelligence asset inside the Eastern bloc for the West.

Kukliński was born to a strong, Catholic Socialist family in Poland; his own father had been a resistance fighter and eventually died in a Nazi German concentration camp. Imbued with a sense of service, Kukliński joined the Polish People’s Army and played a role in the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia alongside the Soviets, Hungarians, and Bulgarians. Combined with the 1970 Polish protests in which 44 protestors were killed and over a thousand wounded, Kukliński offered his services to the Americans.

For nine years, from 1972 to 1981, Kukliński passed highly sensitive material on tanks, anti-aircraft defences, satellites, and nuclear weaponry to the CIA, all of which was incredibly beneficial to the Americans.

Fearing he would be discovered by Polish and Soviet intelligence, Kukliński defected along with his family to the U.S. in late 1981. He was tried and convicted of treason in absentia by a Polish court in 1984.

Though this was eventually downgraded to 25 years’ imprisonment in 1991 and finally revoked in 1995. Kukliński remained in the U.S., periodically visiting Poland, until his death in 2004.

Kukliński’s legacy is quite massive as, in a Cold War sense, the United States was able to better plan combative strategies against the Soviets and the rest of the bloc. In spite of this, Kuklinski is still a rather divisive figure in Poland with a statue of his being defiled three separate times since 2011.

Dimitri Polyakov

Like Penkovsky, Polyakov is another Russian intelligence officer who has significantly impacted the world. Yet, very few know his name.

Dimitri Polyakov, similar to Penkovsky, was commissioned as an Artillery officer and served in World War II before attending the Frunze Military Academy and GRU Training School. One of his first assignments was serving undercover on the Military Staff Committee of the United Nations in the 1950s.

In 1961, Polyakov approached the FBI and offered his services. As for his motivations, while some believe he was resentful of the corruption he saw within the Soviet Union, Victor Cherkashin, a KGB operative, alleges that Polyakov began offering information over the fact that the GRU had denied his medically ill son treatment in New York, resulting in his son’s death.

Over the next twenty-five years, Polyakov repeatedly passed along information to the CIA and FBI. Throughout, he rose through the ranks of the GRU and was assigned to India and Burma as a military attaché to Soviet embassies; during this time, he provided information on Soviet-Chinese relations, on double agents within the Americas, and data on Soviet antitank missiles.

Polyakov retired from the GRU as a Major General in 1980, yet was arrested in 1986 and tried for treason in 1988, being executed that same year. Only later was it revealed that Robert Hanssen and Aldrich Ames, arguably two of the most notable American double agents, revealed Polyakov’s treachery to the Soviets.

Many within the U.S. Intelligence Community regard Polyakov as their crown jewel during the Cold War.

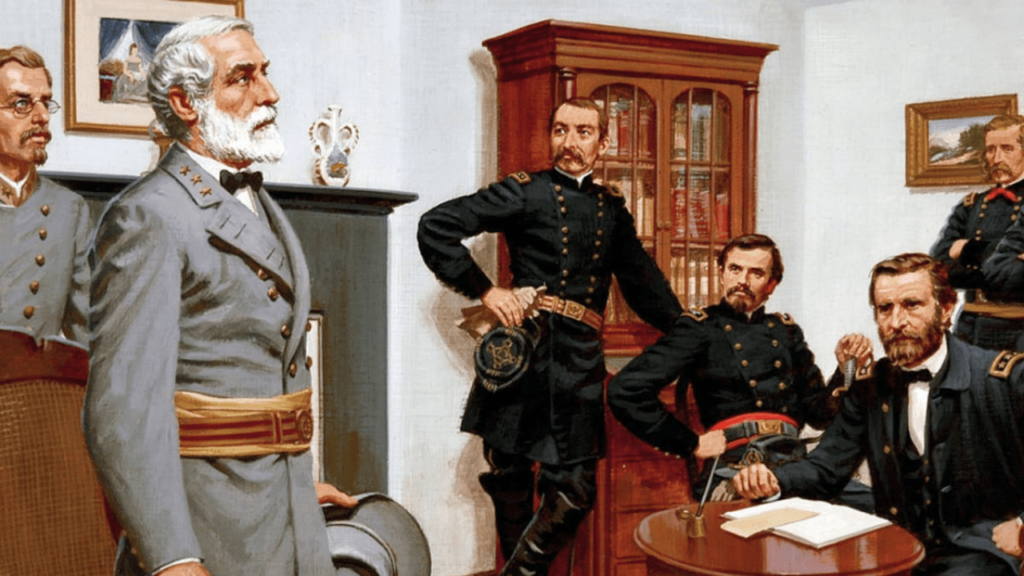

Robert E. Lee

An undoubtedly controversial choice for some on this list, Lee was most surely a traitor, despite being revered by a substantial portion of Americans.

Lee was the son of a prominent Virginia planter family. His father was Henry Lee III, a Major General from the American Revolutionary War and both a Governor and Representative for the State of Virginia.

Supported by friends and members of Lee’s mother’s family, Lee eventually received an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1825 and was commissioned as a brevet Second Lieutenant in 1829 within the Corps of Engineers.

Lee served on the staff of General Winfield Scott and saw combat during the Mexican-American War, holding the rank of Brevet Colonel at the war’s end in 1848. In 1852, he was named the Superintendent of West Point and, three years later, Lee was promoted to full Lieutenant Colonel in the cavalry.

When Lee’s wife’s father died in 1857, Lee took custody of his father-in-law’s plantation and engaged in immense brutality while personally overseeing the administration of the estate.

With war soon to break out between the United States and the secessionist South, Lee was provided with the rank of Colonel in the Cavalry in 1861, before deciding to accept an offer of Major General in the military of Virginia. He was soon made a full General in the Army in August of 1861.

While some have lauded Lee for his tactical and leadership ability, Lee was actually a poor tactician.

He constantly operated on the offensive and rarely took up a defensive strategy, which resulted in heavy casualties and poor morale. He further proved his inabilities at conducting an overall strategy with the Battle of Gettysburg, poorly planning the campaign and not heeding vital intelligence when needed. His actions and overall leadership contributed heavily to the Confederacy’s inevitable defeat.

In retirement, Lee became president of Washington College (now Washington & Lee University), serving in that post five months after the end of the Civil War until his death in 1870.

In more contemporary times, Lee has become a symbol of the South and taken on a type of extreme reverence within military circles, in spite of his traitorous actions and poor command abilities. He also has become a symbol of the right-wing and a key figure within the Lost Cause narrative, with many apologists defending his missteps and heaping lavish praise upon him.

It is without question though, that he betrayed the U.S. Constitution, the United States of America, and the oath he swore to preserve democracy.

John A Walker, Jr.

While there have been many spies throughout history that have damaged the United States, few have done more damage than John A. Walker, Jr.

John A. Walker, Jr. was born outside of D.C. and raised in Pennsylvania. His family life was a tumultuous one, with a series of financial woes and a drunk and abusive father. A high school dropout, he enlisted in the Navy in 1955 and, within 8 years, was a Chief Petty Officer working communications and cryptography aboard submarines.

In 1967, Walker was promoted to Warrant Officer and was assigned to Commander, Submarine Force Atlantic, largely working on communications. At this time, despite a rather illustrious Naval career, Walker was encountering financial problems; he had opened a bar which then quickly shuttered and had a freewheeling lifestyle which resulted in him becoming severely in debt.

Due to this, Walker offered his service to the Soviets. Though initially a member of the John Birch Society, Walker saw the Cold War as a farce and had completely turned his views changed. Over the next eighteen years, Walker provided sensitive Naval documents on communications cyphers, technical manuals, and state ethic war plans. He was paid lavishly for his work and, eventually, retired from the Navy in 1976.

Despite his retirement from the Navy and giving up his security clearance, Walker began recruiting others to form a spy ring; his older brother (a retired Lieutenant Commander and military contractor), a close friend (a Senior Chief Petty Officer and radioman), his son (an active-duty Navy sailor), and had attempted to recruit his daughter (an Army enlistee, going as far as to offer to pay for an abortion so she could continue spying when a pregnancy halted her career).

In 1984, after Walker’s ex-wife called the FBI in a drunken stupor and revealed that her ex-husband had been spying for the Soviets. Initially sceptical, the FBI began investigating and, after much electronic and physical surveillance, arrested all members of the Walker Spy Ring in 1985.

Taking a plea deal to avoid life imprisonment for his son, Walker was sentenced to life imprisonment. He died in prison in 2014 of unrevealed complications.

Walker remains the worst penetration known within the U.S. Navy. His actions and spying led to the Soviets having extreme knowledge of American submarine routes and, had the Cold War turned hot, the Soviets would have had the upper hand in knowing where the Navy’s submarines were in the Atlantic.

As well, while much has been discussed about Walker’s involvement in the 1968 Pueblo incident with many initial media reports citing involvement, some historians and researchers have concluded that Walker was not as heavily involved given the lack of Soviet involvement in the taking of the Pueblo alongside other factors.

Benedict Arnold

One of the best-known traitors in American history, the name “Benedict†is virtually synonymous with the term “Traitorâ€.

Arnold was born a British citizen in 1741 in Norwich, Connecticut the descendant of an English Anglican clergyman on his maternal side and a Governor of the Rhode Island Colony on his paternal side. While the family initially was wealthy, the deaths of two older siblings and his father’s alcoholism resulted in the family becoming impoverished. In spite of this, Arnold was able to become an apprentice to a successful businessman and, eventually, a successful merchant in his own right.

After the Boston Massacre of 1770, however, Arnold went and joined the Colonial Militia, being commissioned as a Captain. Roughly a month after joining, he was named a Colonel in the Massachusetts Militia and helped capture Fort Ticonderoga. That same year, he was commissioned into the Continental Army, was wounded at the Battle of Quebec, and was further promoted to Brigadier General.

In this capacity, he found allies in many high-ranking military commanders, was again wounded in the Battles of Saratoga in 1777 and then made the military commander of Philadelphia in 1778. At this stage of the war, Arnold began to grow bitter and took a wife, pro-Loyalist Peggy Shippen.

Most historians find, due to Arnold’s resentment at being passed over for promotion and receiving honours, his anger at having lost his private business in Connecticut, and the influence of his wife Shippen, Arnold eventually decided to collude with the British.

In late May 1779, through his wife, Arnold made acquaintances with Major John André, the head of British military intelligence in the Americas and, by July, was providing the British with troop movements, arms locations, and capabilities of the Continental Army. By October, however, due to hostile exchanges overcompensation, Arnold ceased the relationship.

In July of 1780, though, partly due to scandal, Arnold was given command of the Continental Army base, West Point and began coordinating with Henry Clinton, Commander-in-Chief of British Forces in North America to surrender the base. On 22 September 1780, Arnold provided plans to André on West Point’s defences, strengths, and total capabilities; while en route to New York, André was captured and the plans Arnold had provided were revealed.

Arnold was able to escape to British friendly New York, arranged for his wife to join him, and received a commission in the British Army with the rank of Brigadier General. He participated in a series of conflicts, yet was largely ignored by higher-ranking British commanders.

After the war, Arnold failed to find steady employment and went into business on his own, struggling and experiencing various bad business deals throughout the Caribbean and Canada. In 1801, at the age of 60, Arnold died after a long period of suffering from Gout and Dropsy.

While Arnold’s legacy in the United States is primarily that of a traitor, in Great Britain, Arnold is viewed more favourably and with grace.

Wilhelm Canaris

One of the key qualities in any spy is the ability to listen and listen well. Perhaps none better exemplify this than Wilhelm Canaris, one of the most notable and impressive, if understated, spymasters in history.

Canaris was born in 1887 in the Kingdom of Prussia and join the Imperial German Navy at eighteen in the (erroneous) belief that he was related to a Greek admiral. Throughout the First World War, Canaris served as an intelligence officer primarily in the South American region, adeptly evading British ships and engaging in a textbook Survival, Escape, Resist, Evade (SERE) strategy to return to Germany. He later served on a U-Boat, undertaking clandestine reconnaissance missions in the Mediterranean and commanding a submarine by the war’s end in addition to being decorated for bravery.

From 1918 to 1935, Canaris served in a variety of intelligence postings, working in Japan at one point and establishing/improving Germany’s submarine capabilities. He also was involved in the 1920 Kapp Putsch, a failed coup against the Weimar Republic.

Like many military veterans of the First World War (and Germans in general), Canaris was a supporter of the Nazi regime. This was even the case after the 1934 “Night of the Long Knivesâ€, a political coup by Hitler and his inner circle against Ernst Röhm and his Sturmabteilung, with Canaris making public statements supporting Hitler and his regime. He additionally was a rabid anti-Semite, a Social Darwinist, and a fervent Nationalist.

Because of his support, Hitler made Canaris the head of the Abwehr, Germany’s military-intelligence apparatus, and was instrumental in providing support to Francisco Franco’s Nationalist faction during the Spanish Civil War. It was during this time that he developed a friendly, yet slightly antagonistic relationship with Reinhard Heydrich, a key figure in the creation of Nazi Germany’s “Final Solutionâ€.

In his position as Abwehr head, he opposed many efforts by Hitler to invade foreign lands and was involved in the 1938 and 1939 coup attempts against the Führer; upon the invasion of Poland in 1939 and seeing firsthand the brutality inflicted upon Polish Jews by the Waffen-SS, he began working against Nazi Germany after having been rebuffed by members of the Army whenever he mentioned the illegalities he witnessed.

Finding Germany to be drifting from what he believed were truly conservative values, Canaris plotted to more strongly go against Hitler and the Nazi regime, providing detailed reports on Nazi war crimes to Catholic priests, halting war crimes committed by Heydrich’s forces, employing enemies of Hitler and the Nazis in the Abwehr, and, in multiple cases, saving Jews from extermination at death camps.

Canaris ultimately was involved in the unsuccessful July 1944 “Valkyrie†plot to depose Hitler, being stripped of his title, tried before a Waffen-SS court, and executed at the Flossenbürg concentration camp a week before the end of the Second World War.

Canaris, initially, was an ardent supporter of the Nazi regime and arguably assisted in enabling some of the worst people in history to enact some of the worst crimes in the history of the world, let alone warfare. However, he realized his mistake and did the utmost he could to try and rectify Germany for the better. Had he survived the War, I argue that German intelligence under his leadership would have been vastly more effective against the Soviet Union and not suffered from the steady employment of Nazi war criminals or Soviet penetration.

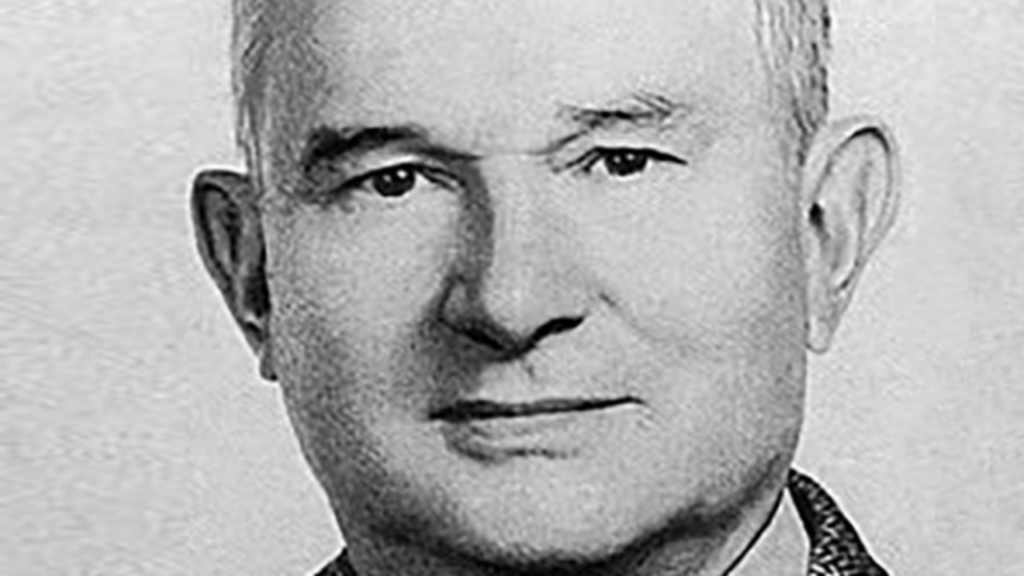

Alfred Redl

For most people, when they think of espionage, famous traitors or defection, they think of the Cold War. Yet, the First World War has a lot of espionage activities and defections present. One of the best and most serious instances of espionage in World War One is Alfred Redl.Â

Redl was born in what is now Lviv, Ukraine, but in 1864 was under the control of the Austrian Empire. Though from a poor family with no significant connections to high society, Redl, through his work ethic and intelligence, was able to gain entry to the Kriegsschule, the Austro-Hungarian Empire’s primary military academy.

In 1882, he gained a commission in the Austro-Hungarian Army and became active in intelligence work, becoming a member of the Evidenzbureau, the nation’s military intelligence service; during this time, he also became a pupil of Arthur Giesl von Gieslingen, the head of the Evidenzbureau and eventual Commanding General of VII Corps.

In 1900, Redl was assigned to the service’s Russian Section, having developed an interest in Russian military affairs. Around 1902, it is believed that Redl began to serve the Russian Empire, setting off what would become nearly eleven years of extremely profitable intelligence gathering for the Russians.

During this time, Redl provided the Russians with war plans, cyphers and codes, maps, and photographs, providing a serious amount of information to the enemy, as well as deliberately underestimated the Russian’s own capabilities, setting the Empire at a disadvantage. Simultaneously, he was assigned the task of finding a mole (himself) within the nation’s intelligence service; he avoided capture in this by appealing to his Russian superiors who provided him with a list of Austro-Hungarians who were also spying for Russia, yet on a far smaller scale.

Due to his efforts at “exposing†the Russian assets in the Evidenzbureau, he was named the chief of counterintelligence and, in this capacity, had access to massive quantities of information while also making immense strides in many technological areas which not only advanced the type of information gained for the Austro-Hungarian Empire but also enabled the Russians to gain the upper hand militarily.

Throughout all of this, Redl was well paid, accumulating an array of luxury vehicles and a great estate outside of Vienna. In 1912, Redl was again promoted to become the Chief of Staff to General Giesl.

In March 1913, however, following a mishap with a letter containing payment, the Evidenzbureau was able to pinpoint Redl as the traitor two months later. Confronting him with his treachery, a short interrogation followed before Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf, the Austro-Hungarian Chief of Staff of the Army, allowed Redl to commit suicide with his service revolver, against the wishes of the Evidenzbureau and Franz Joseph I.

With Redl’s death, the exact motivations for his duplicity are unclear. Many historians and scholars believe that Russian agents in Austria-Hungary uncovered the fact that Redl was a homosexual and used this to blackmail him into spying against his own nation.

Nonetheless, for eleven years, Redl was the crown jewel of pre-war Russian intelligence. His actions allowed the Russians to gain knowledge of what the Austrian-Hungarian plan to invade Serbia was composed of, allowing the Russians to increase their tactical assets in the country. This would prove immensely beneficial in the opening days of the First World War. Redl’s actions are extremely damaging and easily led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of fellow Austro-Hungarians.

In conclusion to history’s most famous traitors

In summary, this in-depth list of famous traitors has explored traitors from militaries the world over and throughout all historical time periods, both contemporary and antiquity. These persons were either members of intelligence services or even civilians, but either had a strong military focus or be an intelligence directorate of military service.