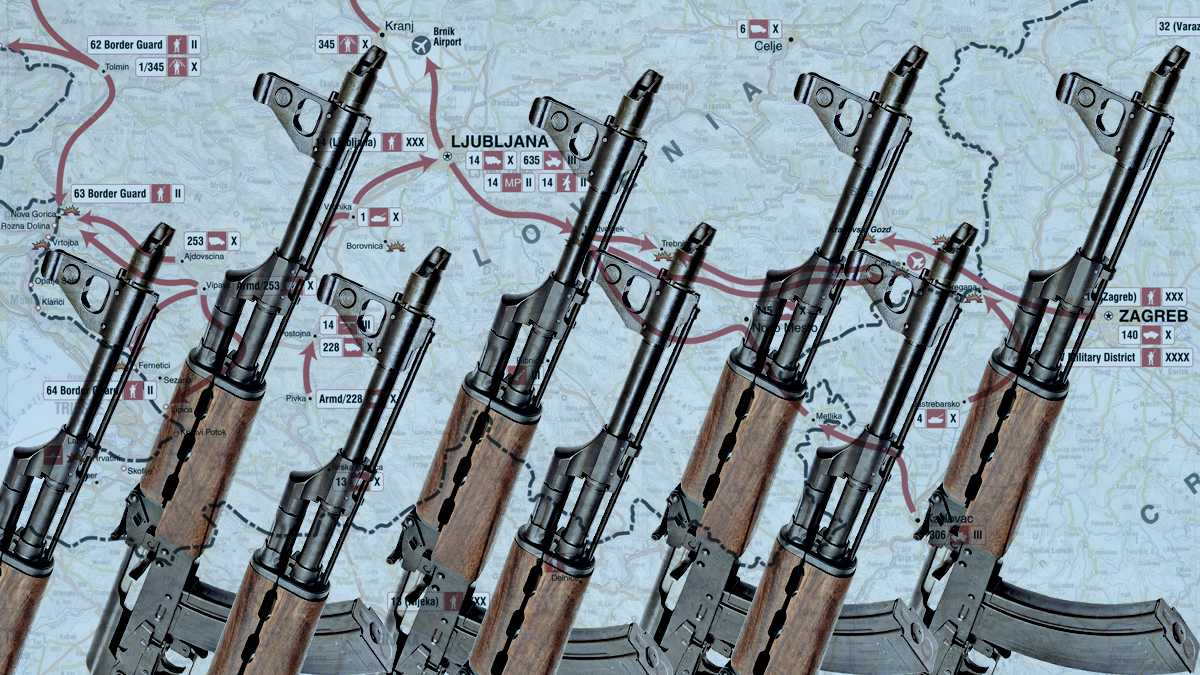

The featured artwork for our latest article on the flow of weapons into Western Europe as a result of the Yugoslav Wars was provided by the highly talented Olivier Ballou.

In the decade between 1991 and 2001, the territory of the former Yugoslavia was engulfed in a plethora of conflicts defined by ethnic cleansing, mass destruction, and chaos. It’s been almost twenty years since the Yugoslav Wars finished and the Balkans are now at relative peace, albeit a divided one. For Western Europe, however, the shadow of the wars in Yugoslavia continues to haunt us with a serious security threat.

In its prime, the Yugoslav People’s Army (YNA) had around 12,000,000 men available for military service. The state began churning out millions of arms to arm these soldiers at a moment’s notice if the territorial defense was needed. As Yugoslavia began to fragment in 1991 the YNA did the same. However, the largest weapons stockpiles and military bases were in the hands of the Serbs making them the dominant force in the region who subsequently waged war on countries like Croatia, and Bosnia who had recently declared independence.

In July 1991 the United Nations placed an arms embargo on the former Yugoslavia in an attempt to stop the carnage. All this did, however, was force embattled Croatia and Bosnia into the hands of a shadowy network of arms traders tied to organized crime who was keen on bringing deadly arms shipments to the former Yugoslavia. In the space of a few months, the region was awash with illegally imported weapons as well as those from the vast stockpiles of the YNA.

According to the Humanitarian Law Centre, over 130,000 people lay dead as the Yugoslav Wars came to an end. Years of relentless warfare, ethnic cleansing, and other barbarism left a feeling of intense distrust between the newly established countries. The weapons used in the wars were not handed over at the promise of peace. As a result, the estimated number of illegal arms in circulation across the former Yugoslavia is alarming. The Interior Ministry of Serbia estimated that there are up to 900,000 small arms units in the country. In neighboring Bosnia, that number is around 750,000 according to SEESAC. Despite only having a population of 2 million the young country of Kosovo has an estimated 450,000 small arms in circulation according to the UN. Statistics reinforced by videos such as this civilian picnic in Kosovo.

As time moves on from the wars many people lose their fondness for weapons, particularly in economic uncertainty. Serbia, Bosnia, and Kosovo are all ranked in the 10 poorest countries in Europe. When well-funded terrorists, criminals, or middlemen appear looking to buy military-grade arms, the right price is around 300 – 500 Euro which is the average monthly salary for many people in Bosnia. The weapons are then sent West along the many highways of the Balkans. Only a small portion of the hundreds of public buses heading for Western Europe every day are checked, not to mention the vans and private automobiles. Local border police and customs are fighting a losing battle and are often bribed. Once the weapon is inside the 26-country Schengen zone of the European Union, smugglers take advantage of the practically frictionless travel across borders.

The most prolific weapon to surface from the former Yugoslavia is the Zastava M70 assault rifle, the design of which is based on the Soviet AKM rifle. The 7.62mm rifle was the standard issue weapon in the Yugoslav People’s Army in 1970 and it’s estimated that over 4 million were produced. Corruption was common in the gun factories to such an extent that common joke amongst factory workers was ‘’when you manufacture weapons, one is for the government and one is for you.†For a terrifying case study of what these weapons can do when they fall into the wrong hands and hit Western Europe, we only have to look at the wave of catastrophic terror attacks that swept across France in 2015.

During the violent rampage at the offices of Charlie Hebdo carried out by two al-Qaeda members known as the Kouachi brothers in January 2015, both men were armed with Zastava M70 rifles. 12 people were ruthlessly executed during the attack. The rounds they were killed with? All purchased by the terror cell or middlemen in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The 7.62mm rounds were originally manufactured in 1986 by Igman Company, a state-owned factory in the town of Konjic south of Sarajevo.

In November of the same year, an ISIS cell attacked a concert at the Bataclan Theatre as part of a larger coordinated terror attack across Paris. The terrorists entered the building and opened fire with automatic weapons. In the aftermath, 90 innocent people lay dead. Alongside the three dead attackers was a Zastava M70 assault rifles from the former Yugoslavia, an AK47 from neighboring Bulgaria, and a Chinese made AK47 that likely originated from Communist Albania before falling onto the black market during the Albanian Civil War and subsequent War in Kosovo.

In contrast to the attacks on 9/11, modern terrorists have figured out how to unleash maximum carnage and terror with minimal equipment. After the Madrid train bombings in 2004, the massacre at the Bataclan was Europe’s deadliest terror attack of the 21st century. Despite being armed with suicide vests, the majority of victims fell to the smuggled assault rifles carried by the terrorists. Three weapons were all that was required to cause absolute havoc.

The ammunition used by the terrorists in Paris was manufactured in 1986 by Igman Company, a state-owned factory in the town of Konjic south of Sarajevo. The bullets were manufactured 30 years ago, so it would be impossible to explain how they reached France.

Zivko Marjanac, deputy defence minister of Bosnia

The task of efficiently tracking and stopping the flow of illicit arms from the former Yugoslavia is almost impossible. The black market for weapons operates on a system of very basic supply and demand. It’s not containers of weapons coming into Europe but rather a case of “micro-trafficking†where just a few weapons are smuggled in making it much more difficult to track. In contrast to drugs, which are consumed in large quantities and require regular resupplying thus raising the likelihood of being intercepted, guns, especially hardy Eastern European models like the Zastava M70, last for years and once inside Western Europe they pose a lethal and persistent threat until seized by the authorities.

The horror of the attacks in Paris created a spotlight on the French connection to military-grade arms of the former Yugoslavia. It subsequently pushed the EU to make more aggressive laws in order to weaken the flow of arms from the era of the Yugoslav Wars. This included marking weapons to make them easier to trace as well as deeper integration between the EU and Interpol’s centralized tracking system, which records all firearms lost, stolen, or trafficked.

Serbia and France, the two key characters of the ‘French Connection’ between weapons from the Yugoslav Wars and the attacks in Paris, signed a deal to form a joint task force to investigate illicit arms smuggling across Europe. The deal materialized in an enormous two-day Interpol-led operation which saw 5,000 police officers mobilize across all of the former Yugoslavian republics. However, the operation only resulted in 22 arrests and the seizure of 40 firearms and six kilograms of explosives. Only a few million more to catch.